Every writer has favorite writing devices to effectively convey their story. I have discussed several in my previous posts, but one that has helped flesh out my characters many times is the Doctor Dolittle Effect. In other words, my characters reveal their inner-most thoughts with animals. But, unlike Doctor Dolittle's patients, my animals do not answer.

|

| Hugh Lofting's Doctor Dolittle converses with animals |

A standard novel writing scheme to convey a character's thoughts is with italic font or muttered statements. While both are acceptable, they can become redundant, if not to the reader then to the writer. Plus, statements spoken aloud lend a dramatic effect cold description cannot match.

Akulina and Her Cow

Akulina is a single mother raising her two sons in the Russian village of Unkurda. While she does have female friends, she usually keeps her deepest thoughts to herself. Only when she is alone with her animals does she verbalize her thoughts and feelings. In this excerpt from

Slogans: Our Children, Our Future, Akuliina tells her milk cow,

Belyanka, about the boys' erroneous belief that owning a cow makes them rich and an enemy of the people.

***

“Did you know you lived in a palace? Ah, yes, Belyanka, I have it

from a very good source.” Akulina's swept her arm around the cow's

surroundings, a simple wooden cowshed, wide enough for two stalls and

strong enough to keep out the wind and snow but little else. “Yes,

we are rich. We are aristocracy, nou? Soon I will be invited

to the grand balls in the estates of the pomieshtchnik.”

Akulina pulled a hot stone from her apron and rubbed it with her

hands. “What do you think I should wear? The red gown with the

ermine fur? Perhaps the blue one with golden trim and diamonds? Of

course, how foolish of me. I have but one dress. Perhaps it hangs a

bit loose, but it is still a good dress, is it not Belyanka?”

***

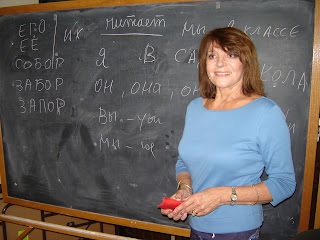

|

| Akulina speaks to Belyanka while milking |

Akulina and Her Cat

Through this sarcastic discourse with her cow the reader learns Akulina, though poor, has a wry sense of humor about her sons' attitudes. Later in the story, Akulina pours out her emotions to her murdered cat,

Petruska. The scene ends with Akulina breaking down and seeking

Belyanka's comfort.

* * *

Akulina picked up the cat's limp form, cradled him in her arms and

stroked his fur. Petrushka's head dangled at an unnatural angle as

Akulina carried him to a corner of the cowshed. His once bright

eyes, glazed over by death, again asked, “Why did I have to

die?”

“Superstition,” Akulina replied in answer to the cat’s silent

question. Did people believe a simple cat could be the devil just

because it once lived with a wise old woman and now lived with

someone who could cure? “Superstition and ignorance, Petrushka.

Superstition and ignorance killed you.”

Akulina knelt down and began to remove straw away from the wall.

“You stay here until I find you a fit burial place. You were a

good cat, Petrushka, but I don't want the boys to know.” Akulina

covered the body with straw and patted it down. “'Where's

Petrushka?' they will ask. 'Oh,' I will reply, 'he wandered off.

You know cats.'“ Then she began to tremble.

Tears splashed down her cheeks and her body began to shake. She heard

herself wailing uncontrollably. Her sobs came in gasps and her

shoulders ached from the spasms. “It's just a cat,” she choked.

“Just a cat.” But she realized it was more than a cat for which

she wept. All the pain and suffering she had shut away breached

their walls and came flooding back. She cried for the boys who died

in the woods and those who passed from the winter sickness. She shed

tears for the men at the gallows, those buried in the meadow, and for

Old Rosina. Her tears were for her mother, may God rest her soul,

who died from her mistake. She cried for her father's burden, Kataya

and her sons' loss of innocence and the world still to come.

Akulina stumbled over to Belyanka's stall and held the cow with her

arms. She needed someone or something to hold. She did not want to

be alone. Akulina pressed her face against Belyanka's neck and

continued to weep.

* * *

Boris Speaks To Dead People

If your antagonist or protagonist has a dog, horse or any animal, use it as a sounding board. Express whatever is on your character's mind through them. Sometimes the object of your character's soliloquy may not even be animate. In

Slogans. Boris often sits alone at the table and argues with his dead wife attempting to justify his decisions.

|

| "I'm sorry, Maria." (Alfred Eisenstaedt,) |

* * *

“I was wrong about those in charge. I wanted to believe it did not

matter. I told moy droug, 'governments, bah. They are all

the same. They're all crooked.'“ Boris' words were now flowing,

however unsteady. “Fedora Popovich was correct. Hutava is no more

and Siberia is our home. We have no choice but to live here.”

Boris stared down at his bottle and shook his head. “I am between

the hammer and the anvil, or so they say. The Whites kill the poor

and the Reds kill the rich. You know I am not rich, Maria, and I

must apologize for what I must do”

* * *

The Doctor Dolittle Effect can be a handy tool in writing your novel. For your writing and reading enjoyment, add it to your arsenal and give it a try.